Why put a price on nature?

February 18, 2011 Leave a comment

“Should we put a price on nature?”

I’ve heard this question come up a fair amount recently in discussions here and there, so it seems like it is a topical one to cover. There are many tricky hidden barriers embedded in this question. So, if not addressed, this little point of inquiry can become a major stumbling block that prevents well meaning people from moving forward with integrating valuing Ecosystems Services (ES) into the way we do things. While we’ve piloted market mechanisms to lower carbon and put in other Payments for Ecosystems Services (PES), there has been a lag in mainstream uptake, and this little question just might be a major stumbling block in this uptake (well, aside from certain industry lobbying, disinformation campaigns, ignorance and climate change denialism). I should know, because I stumbled over this one myself for a few years. (I can be a slow learner.) So, I think it’s worth unpacking and giving my two bits on. Hopefully this will open up some discussion on it, so please feel free to make comments below.

So, what are the embedded thought barriers in the question “why put a price on nature?” They go a little something like this:

- “Nature is priceless”: Nature has intrinsic value which makes it priceless, so it is at best trite and at worst ethically wrong to put a price on it.

- “Nature is bigger than us”: We are a part of nature, not the other way around. So we shouldn’t put a price on it because it isn’t ethical as it would be wrongly self-centered of us to do so, and because it just doesn’t make sense. Nature is bigger than us and our economic systems, so there is something wrong in doing this.

- “It will lead to abuse”: It is wrong to put a price on nature because it will be exploited by those with perverse incentives, like rich corporations did with water in Bolivia. They monopolized and put a price on what should be a free resource. People should have a right to fresh air and potable water. They, should not have to pay for it, especially not beyond their means.

Can you think of any other embedded barriers behind this question? Let me know if you do.

As far as addressing the above thought barriers, here are some answers that I have come up with for myself:

1. “Nature is priceless” argument

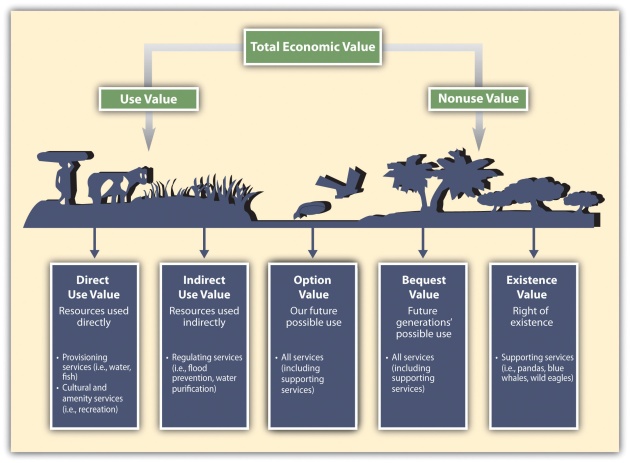

Now one could go all deep and philosophical on this question, but one can also address it by sticking to some reasonable basics. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment is one of the activities that has launched much of the current work to value Ecosystem Services, hence advocating for ‘putting a price on nature’. As they have stated, we can value nature BOTH intrinsically and economically through some sort of valuation system, such as the one below by the FAO.

So, just because I deeply value the mountains and forested watersheds in my region, doesn’t mean that I cannot also condone putting a reasonable economic value on them to serve as a barrier to protect them from being externalized, and thereby depleted or lost.

Finally, let’s get real here. Let’s get to the point.

Humans HAVE ALREADY put an economic price on nature. We’ve done this for millennia as part of the very growth of our economic trade systems. What is the value of lumber, of fuel, of fish, of other wild harvested items? These prices exist, have existed, and will continue to exist unless one advocates for anarchy.

The whole point here it to put a value on the Ecosystem Services that have NOT yet been priced, and hence have been externalized from our ledger books. Economists made assumptions about these ES, thinking that they couldn’t be depleted. But they were wrong, and so we have not had appropriate market checks and balances to subside and stop extraction when critical thresholds of take either overwhelm a flow or reach the capacity of a natural resource to replenish itself.

In the quantitative models that appear in leading economics journals and textbooks, nature is taken to be a fixed, indestructible factor of production. The problem with the assumption is that it is wrong: nature consists of degradable resources. Agricultural land, forests, watersheds, fisheries, fresh water sources, river estuaries and the atmosphere are capital assets that are self-regenerative, but suffer from depletion or deterioration when they are over-used. (I am excluding oil and natural gas, which are at the limiting end of self-regenerative resources.) To assume away the physical depreciation of capital assets is to draw a wrong picture of future production and consumption possibilities that are open to a society. – Partha Dasgupta, 2010

So this isn’t really about the question of putting a price on nature or not. We’ve already done that. It’s about making better assumptions about how we do it. It’s about not being negligent on what we are factoring into the equation. We need to price the right things the right way so that we do not erode critical ecosystem services, deplete natural capital beyond the point of replenishment, and erode the future productive base of society.

2. ‘Nature is bigger than us’ argument

Yes, we are a part of nature. Nature’s systems are bigger than us. In fact, the history of scientific thought in the area shows that we used to also believe that nature was SO big and powerful that there was no way that puny humans could impact Earth’s systems. However, although scale is an important factor to consider, it’s not just about scale but impact.

So, we need to ask the question, “Regardless of scale, do humans impact Earth’s systems, and is our impact significant enough that we might deplete or destroy those systems?”

And the answer to that, unfortunately, is ‘yes’ and ‘yes’ and ‘yes’. Research over the last thirty or forty years has shown that biotic systems, and especially those biological creatures called humans, impact physical Earth systems in ways we just didn’t fathom possible before. Part of this knowledge has built up as a result of things like James Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis feeding into the development of Earth Systems Science as a discipline. But mostly it has been supported by the incontrovertible evidence of the impacts that humans have made on the natural resources and systems of this planet. There is no denying that we have changed the face of the planet with our development, our agriculture, our cities, our mines, our natural resource extraction, our travel and on and on. And, in so doing, we have sometimes caused some serious impacts, including causing previously very strong natural resource systems to collapse, such as the cod on the east coast of Canada.

And then we have the additional things that add up in our global commons. Things like acid rain, the ozone hole, ocean acidification and eutrophication and, finally anthropogenic climate change. All, proof of principle that humans not only impact local to regional ecological systems, but that collectively we impact the large scale global systems on this planet–like climate. From local to regional to global scales, from boundary layers over cities, to recycling of rain over forest systems, to global warming due to mounting greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, we have and continue to change Earth’s climate.

And because humans have these impacts, we need to take time to understand them better, but we also need to take the necessary steps–with the information at hand–to be better stewards of the systems that we impact. We need to manage risk by preventing ecosystem services from depleted or destroyed. We did this with successfully implementing market mechanisms to mitigate acid rain. I believe we can also do it with tigers, with wild fisheries, with water resources and finally, and perhaps especially with climate. (And it’s about time our North American governments stepped up to the plate to put in regulations to do so.)

In not implementing market mechanisms (has anyone found any more efficient and implementable solutions than market mechanisms?) to address this significant risk, in operating as we have been, what are we left with? We are left with still externalizing from our economic books these losses, and jeopardizing what we once thought were unshakable and untouchable foundations of not only our future economic and social growth, but potentially life on this planet.

That’s just not a gamble I’m willing to take.

3. “It will lead to abuse” argument

It is a well established fact of history that we can be abusive. Many humans have, do and will continue to behave in selfish and destructive ways. We have to expect that with anything humans do, that some of them will cheat. But, we can also be creative, constructive and cooperative, and most of us fall into the latter category. Society would fall apart if most of us didn’t follow the rules.

The key here is that while humans are being constructive or destructive, they use the tools at their disposal. I can use a hammer to build something, protect something, or restore something. But, I can also use it to destroy something or hurt someone.

So, we have to be careful here.

If we develop new tools to price Ecosystem Services, and those tools are used improperly and unjustly, then we need to ensure that we blame the humans that wielded the tool–not the tool itself. And we also have to adjust our systems to safeguard that the tool gets used appropriately and constructively, as it was intended. We need to adjust our regulations, put in legislation, have adequate enforcement and put in watchdogs.

So, what is putting a price on nature? It is just another tool. That’s all. A mechanism. And even if there have been cases of people using it inappropriately, its proper function is to restore and protect natural ecosystems while also working with and protecting local vulnerable communities, particularly indigenous peoples. So, we need to devise policies, including enforcement mechanisms, to ensure that the tool is used as it was intended.

So, I would argue to keep the tool, stop preventing its use because of abuse and take care of the perpetrators the way we do in other cases. And we need to do this soon because the business as usual scenario, with our previous tool kit… Well, it just hasn’t been good enough.